News writer

If it weren't for the lottery and my family's unimpeachable luck, I wouldn't be here.

My family won the lottery. Not Powerball or scratch-offs.

They won the lottery in Czechoslovakia in the 1900s. I believe that it later saved their lives, and ultimately, in a way, put me on the planet.

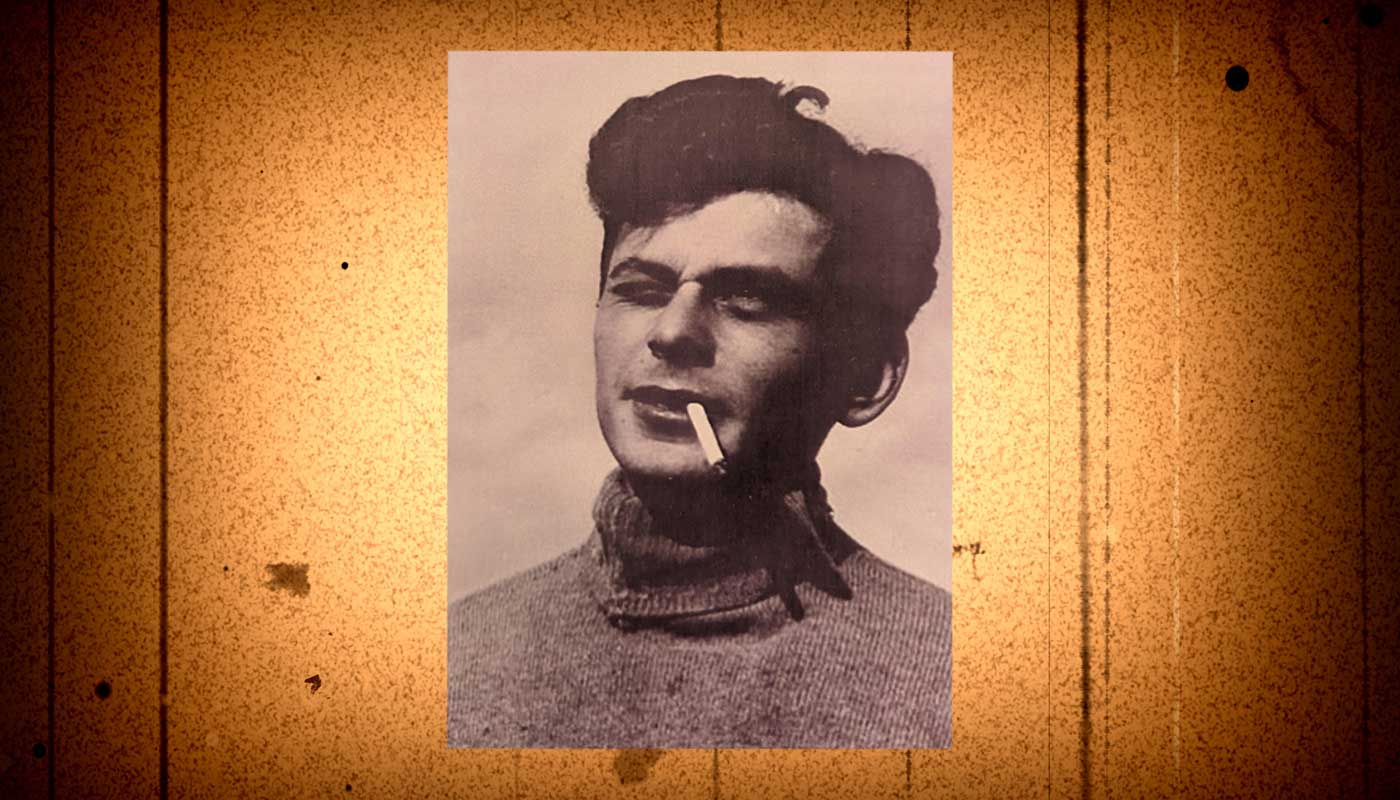

As an American born in the Bronx, I don't personally have strong ties to this footnote in my family history. My Czech-born, Jewish grandpa Ota Bondy did, though - and I knew him very well until he died of a heart attack in 2012. He wrote all about it in a 300-page thrill ride of an autobiography.

Ota's luck

What I did know was this: Ota had a lot of luck.

He was the type of guy who survived wildfires, brutal car accidents, and heart attacks (until that last one). He was a family man where it mattered, and reckless whenever he could get away with it - making him truly the funnest grandfather ever.

But as I got older, his luckiest break was eventually revealed to me: he'd escaped the Holocaust.

Compared to the rest of his extended family - and the majority of Jews in Czechoslovakia in the 1930s - he'd benefited from an incredible series of lucky breaks, including a lottery win generations earlier. It was this fortune that would usher him, a teenager, through a clandestine adventure through Portugal, Italy, France, Austria, and even Nazi Munich, eventually to relative safety in England, and a boring - but calm - life on a chicken farm in New Jersey.

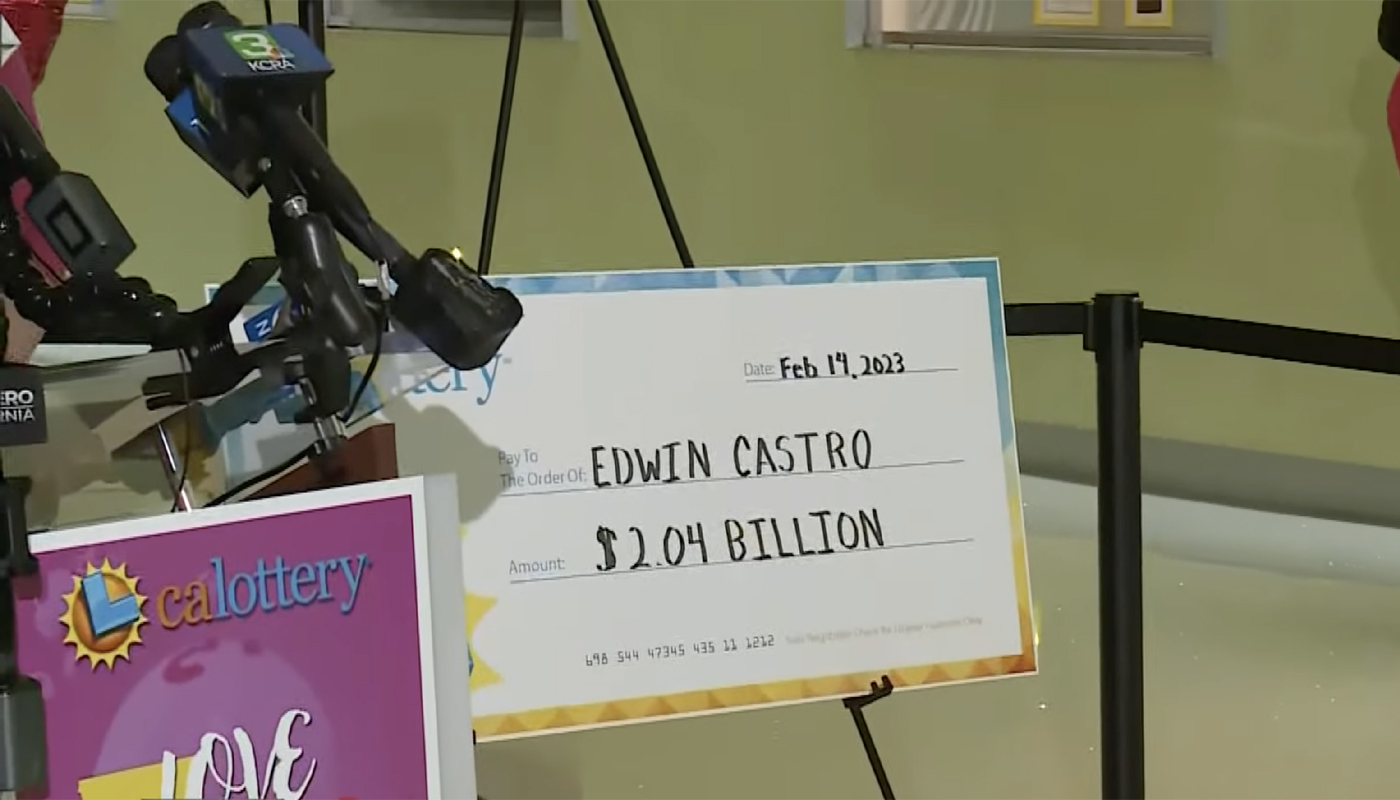

The lottery win

In the early 20th century, Ota's maternal great-grandparents lived in a small town called Polna, which became known as the site of a deadly pogrom against the Jews. My relatives never spoke about the pogrom, but they clearly survived. That side of the family ran a small shop and lived simply, while the other side - Ota's paternal side- were peasant farmers.

Soon after, everything changed. His maternal side - his great-grandfather Emanuel - won the national lottery. Ota wrote in his autobiography:

The European lotteries back then were structured differently than the lottery in the United States today, but the object was similar. You would buy a 'lottery bond' for a large amount of money as an investment. This was a permanent document with a unique number. Periodically, the drawing was held and winning numbers were announced. The lottery bond could be sold the way stock certificates are sold nowadays.

In other words, the lottery and national bond investments were rolled into one. It's a great idea for the state, though it seems far more complicated than buying a ticket at a corner store. This was Kafka's time and place, after all.

Whatever the lottery format, my grandpa wrote, “The winning prize was substantial and changed the fate of the whole family.”

Stepanka, the daughter of the lottery winner (Ota's grandmother - it's hard to keep straight) would live in a large house with staff. She married a man named Otto who was cash poor, but he descended from a famous local rabbi - and thanks to his wife's lottery dowry, he became a lawyer.

Later, the family used their wealth to buy a jewelry case and watch business, and ran it successfully. Before the Nazis came and took everything, Ota was quite the spoiled rich kid. He was always getting into trouble and being expelled from school for drunken antics. He didn't think he had a care in the world.

The great escape

Ota had another series of lucky breaks. He was never arrested, even though this was his attitude in the late 1930s:

After soccer, I would go to a nearby Ping-Pong table (ignoring the 'Jews not welcome' sign) to play table tennis with other customers for an hour or so…Later, I would often end the day in a movie house, again decorated with a 'Jews not welcome' sign…Since my mother didn't have any time to cook, we ate out often in restaurants again, where Jews were not officially welcomed.

(His autobiography helped me understand his later disdain for authority and why he always flagrantly argued with cops all the time.)

His sister Helena was able to get a spot on Kindertransport, a famed escape route for Jewish children during the Holocaust - though Ota wasn't able to get placement because “nobody wanted a naughty teenaged boy,” according to him.

His father, Rudolph, was already in England on a business trip when the Germans took hold, so he was safe and frantically watching the news.

Perhaps Ota's biggest lucky break - besides the lottery - was that he had a resourceful mother, Anna, who foresaw the horror and made arrangements to flee with him from Prague to England, even when nobody else believed the political situation would deteriorate. His entire extended family - all the other Bondys - thought things would improve. All of them, including Stepanka, were murdered in concentration camps.

Because Ota's family had won the lottery and made wise business decisions, Anna was able to get him to safety. Realistically, and tragically, it took money to create forged documents, to switch identities with Italian Gentiles, to take trains all over Europe, and to carve out safe harbors in seven different countries. The logistics were unimaginable. Money was the only way.

How I got here

And it took even more luck.

The Nazis didn't look in the false bottoms of their suitcases on their journey, which contained critical escape funds.

When they finally made it to England and reunited with his sister and father, the bombs overhead didn't kill him.

Nor did the shells when he enlisted in the Czech army tank division.

Nor did the iron curtain, which consumed Prague in the 1940s.

By then, the family had had it with Europe. He, his sister, and their parents sailed to the US with their health intact, though they had to start over with few possessions and no comprehension of English. The family moved to New Jersey and ran a chicken coop, which was part of a government Jewish refugee placement program. Ota met my grandmother, who had survived Kristallnacht in Germany. They married - in what you can imagine was a wild, mentally taxing union, though I found their yelling hilarious as a child - and they had my dad.

And there you have it.

The luckiest family in the world

My family isn't religious, but I see this story as nothing short of a miracle. I've always attributed their survival to Anna's fortitude and to Ota's blase, adventuring soul. But, if I'm being truthful, without the Polna lottery jackpot win, it's highly probable that my family would have remained poor through the generations, which would have spelled extinction. I would never have existed to write about it at a time when these stories are needed more than ever, and can't be forgotten. Without that cash influx, my family may not have passed on their shrewd business sense, which I use every day to provide for my daughter. I may be lucky, but I still do my best.

We usually hear stories about the winners, but not about the descendants whose lives have been impacted. I'm grateful for my family's luck. But I would love to live in a world where everyone who's suffering could win the lottery - whether now, or generations later.

Comments