News writer; Opinion columnist

Every lottery player has a system. Some play the same numbers every time, others consult their zodiac signs, and some players only buy tickets on certain days or from certain stores. The one thing that all of these systems have in common is that none of them work.

Absent buying every ticket for a lottery drawing (which has happened), there's no real way to tilt the odds of a lottery in your favor. Or, to be more accurate, there's almost no way to do it.

From multipliers to free games, modern lottery draw games like to add incentives that will encourage players to buy more by offering them additional opportunities to win. However, if those bonuses aren't calibrated correctly, they can actually tilt the odds in the players' favor.

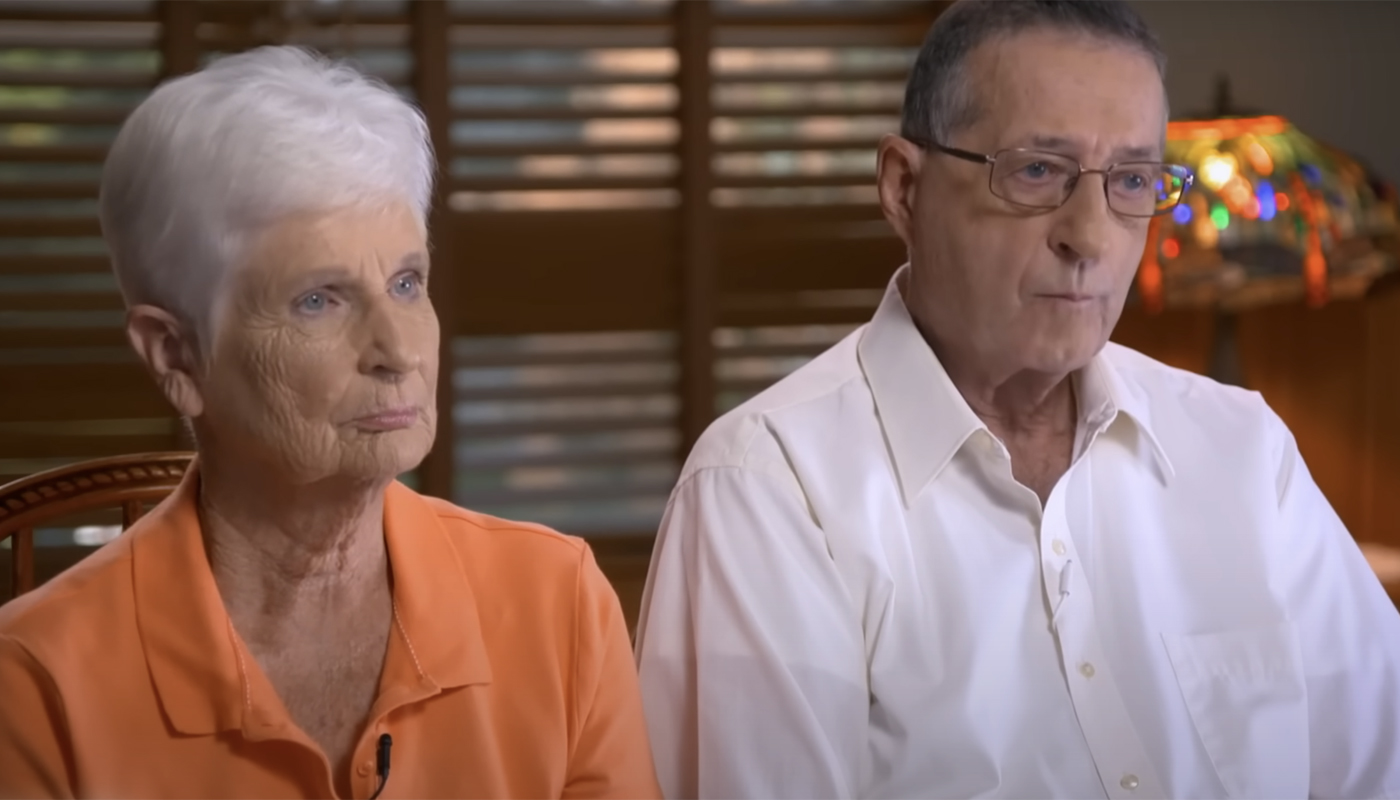

Jerry and Marge Selbee of Evart, Michigan, won millions of dollars by outsmarting a lottery game with a bonus structure that was more generous than its creators realized.

The Rolldown

The key to understanding how a pair of senior citizens from the Midwest beat sophisticated lottery commissions starts with the Rolldown.

In big multi-state draw games, such as Mega Millions and Powerball, the jackpot is cumulative. This means that each time there's no winner for the top prize, it rolls over to the next drawing until someone finally picks the winning numbers.

That's why some lotteries can offer massive billion-dollar jackpots.

However, some games use a roll down system. That means once the jackpot reaches a certain value and no one wins, the accumulated money will be paid out to lesser winners.

In a Rolldown drawing, someone who only picked five of six numbers could win a prize ten times larger than they would for a non-rolldown drawing. That meant a ticket that would have won $5 in a regular drawing could win $50 in a rolldown drawing.

The increased value of these small-win tickets was the key to Jerry and Marge's realization that they could guarantee lottery wins.

Jerry and Marge

Jerry and Marge were high school sweethearts with six children. They ran a convenience store in the small town of Evart, Michigan, for twenty years. The store had one of the state's first lottery ticket machines, but neither Jerry nor Marge played the game because the odds of winning were so unlikely.

After they sold the store and retired, Jerry, who was 64, needed something to keep himself busy. One day in 2002, he noticed an advertisement for a new lottery draw game called Winfall while visiting his old store.

A ticket for Winfall costs $1, and players need to pick six numbers between 1 and 49. While correctly picking all six numbers would win the jackpot, guessing five, four, three, or even two numbers would win a smaller cash prize.

The odds of winning the top prize were extremely low, but Jerry saw that the odds of picking three out of six numbers were just 1 in 54 and that the odds of picking four numbers correctly were 1 in 1,500.

What really caught his attention, though, was the Rolldown feature that kicked in once the jackpot reached $5 million.

Jerry always had a head for numbers, and he realized that because of the increased value of the non-jackpot winners in a Rolldown drawing and the much higher odds of picking three, four, or five numbers, if he bought enough tickets, statistically, he was guaranteed to have enough partial winners to collect more money than he was spending.

His plan would only fail if someone won the jackpot, but according to his calculations, there was over a 90% chance that no one would.

Bumps in the road

The first time Jerry tried his scheme, it didn't work. He purchased $2,200 worth of tickets but only won $2,150, for a loss of $50. After his first failed attempt, he realized that he needed to bet more to increase the odds that he would pick winning number combinations.

On his second try, he purchased $3,600 worth of tickets, and this time, he won back $6,500. He tried again, buying $8,000 worth of tickets and winning back $15,700. Now, he knew that his system worked and that the more tickets he purchased, the more likely he was to win.

While on a camping trip with his wife in Alabama, Jerry finally told her about his system. Instead of being mad that he had risked so much money, she was thrilled that he had found a way to beat the system, and they decided to work together to make as much money as they could.

The system

Jerry's system was sound, but it wasn't easy to carry out. That was mainly because there was no easy way to buy and print the thousands of tickets he needed for his plan to work. He had to drive to a liquor store far from his home and buy from a machine that could print just ten tickets at a time.

He would spend hours in front of the machine printing huge piles of Winfall tickets and bundling them with rubber bands. Then, once the drawing was held, he and Marge would sit in front of their TV and sort through thousands of tickets twice to find the winners.

After filtering out their winning tickets, they would take all their losing tickets, place them in watertight storage bins, and stack them in their barn to prove to the IRS that the deductions they were taking for their non-winning tickets were real.

The plan worked, and they consistently won tens of thousands of dollars in every rolldown drawing. However, when Jerry realized they could win even more money if they bought more tickets, he decided to form a corporation, GS Investment Strategies LLC, to use as a front for a buyer group. He sold shares to his close friends and family, and soon, everyone was making money from Jerry's rolldown scheme.

Gone to Boston

Everything worked just as Jerry and Marge had planned until, in May 2005, the Michigan Lottery dropped a giant bomb on their perfect plan by discontinuing the Winfall game. Jerry and Marge were distraught, not only because they had been making money but also because they had been helping their friends, some of whom had been able to put their children through school with the profits they made from GS Investment Strategies.

Then, Jerry's friend, who was also a member of the buyer group, alerted him to something he had discovered in Massachusetts. The lottery there also had a game called Winfall that was similar to the Michigan version.

Tickets for this game cost $2 each, and the Rolldown triggered at $2 million instead of $5 million, but the odds and rules were similar enough that Jerry and Marge's plan would still work. The only issue was that Jerry didn't know any Massachusetts Lottery retailers who would let him print thousands of tickets over an entire day.

His friend introduced him to Paul Mardas, who owned Billy's Beverages in Sunderland, MA. Jerry made a deal with him: In exchange for using his lottery machine as often as needed, he would give Paul a stake in GS Strategies.

Jerry hated dealing with airports, so the next time there was a rolldown drawing in Massachusetts, he packed up his pickup truck and drove the 700 miles to Billy's Beverages in 12 hours. Once there, he spent an entire day printing tickets, and just like that, he was back in business and making money.

The competition

Once Jerry proved that his system could still work in the Bay State, he and Marge would make the half-day drive to Billy's every time there was a rolldown drawing, which was approximately every six weeks.

Despite winning millions by this point, they stayed in the same Red Roof Inn on every trip. Their stays lasted approximately ten days because that was how long it would take them to sort through the approximately 70,000 tickets they purchased for each drawing.

To help Jerry out, Marge made a deal with the owner of a diner called Jerry's Place. In exchange for allowing her to spend an entire day printing lottery tickets, she would allow him to become a member of their lottery-buying group.

Everything was going well until a new complication emerged. Jerry and Marge were still winning, but their profits weren't as high as they used to be. They quickly realized they weren't the only ones taking advantage of the Winfall drawing.

Other people had discovered the same rolldown loophole, including a group of MIT students buying hundreds of thousands of dollars of tickets for each drawing. This meant that the same amount of prize money was being paid out to more and more winners, reducing each group's total profit.

The groups soon found themselves in competition with each other. The MIT group even tried to force everyone else out by buying so many tickets for a single drawing that it would trigger a Rolldown before it could be publicly announced.

The end

The state commission carefully tracks all lottery ticket buying in Massachusetts, and employees noticed unusually high buying at just a few stores for the Winfall game.

They even sent investigators to watch Jerry buy tickets, but after watching him work the machine, they concluded that he wasn't breaking any rules by buying thousands of tickets.

Still, someone leaked information about the groups to an investigative reporter from the Boston Globe. The reporter eventually uncovered the identities of everyone involved and even tried to interview Jerry and Marge, who refused to comment.

The Globe published a massive story about the buyers' groups and made it seem like they were doing something nefarious because some of the retailers were breaking the rules to help the groups buy so many tickets. Initially, the lottery commission failed to act on the Globe's report, but when it was brought to the attention of the state treasurer, he ordered them to take action, and it was announced that Winfall would be coming to an end.

By 2012, the game had been shut down, and there weren't any more rolldown drawings to exploit, so the buyer groups broke apart.

Back home

While the scheme was finally over, Jerry and Marge still had to consider it a success. Investigators believe that they personally won $20 million and made a profit of around $5 million after deducting expenses and taxes. They also paid millions more to their fellow investors.

In 2022, Hollywood came knocking and made a movie about their exploits called Jerry and Marge Go Large, starring Bryan Cranston and Annette Benning.

So, what did they do with all of that money and fame? Not much, as it turns out. Jerry got himself a new pickup truck and a fishing boat, but they kept the same house, went out to eat at the same restaurants, and never took any big luxury vacations. Marge wouldn't even buy a dishwasher, and she still washes everything by hand.

Ultimately, the real fun for them wasn't the money; it was beating the system and helping out their friends and family while doing it.

Comments