News writer; Opinion columnist

Two hours before the Pennsylvania State Lottery conducts its official drawing at WITF Studios in Harrisburg, six people, including two lottery officials, two accountants, and two senior citizens, open the doors to the high-security vault where the lottery equipment is stored.

Just opening the vault door requires activating a biometric scanner. Cameras mounted both inside and outside the vault track everyone's movement. The game's balls are stored in a second locked safe, which only the accountants have the combination to. Each ball is equipped with a microchip, so its location can continuously be tracked.

If all of this seems like a lot, that's because it is, and for good reason. While today, Pennsylvania treats its lottery equipment with the same level of security usually reserved for nuclear codes, in the 1980s, it used only slightly more protection than your dad's liquor cabinet.

That's how a local gameshow host almost got away with rigging the lottery and stealing more than one million dollars.

What's your number?

Pennsylvania has one of the most passionate groups of lottery players anywhere in the country.

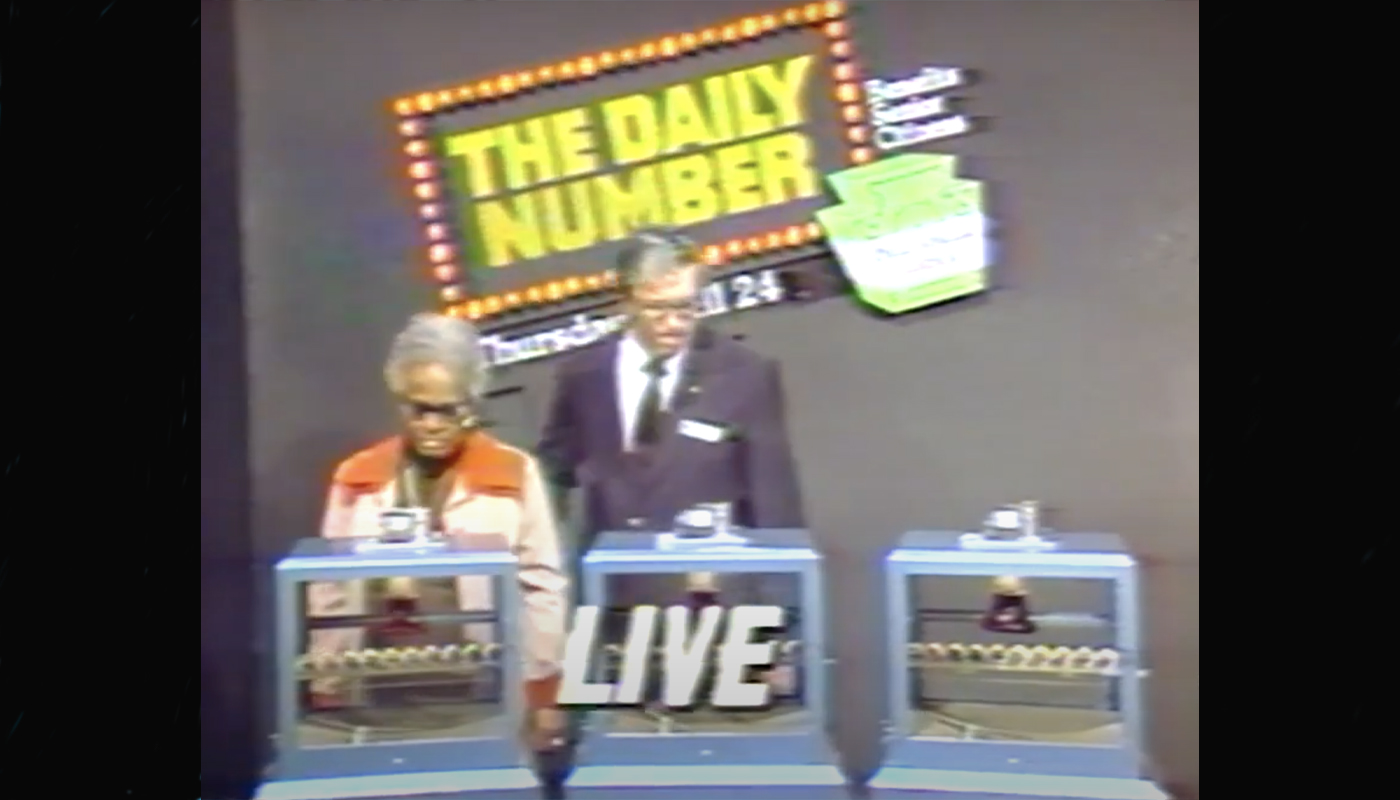

That's why, in 1981, the highest-rated TV show at 7:00 p.m. in the Keystone State was the drawing for The Daily Number, a lottery game in which players had to pick three numbers between zero and nine.

Nick Perry, a local media personality famous for presenting shows like Bowling for Dollars, was the host of the daily drawing.

The game featured three drawing machines, each containing a full set of numbers so that the same number could be selected three times in one drawing. The numbers were written on ping-pong balls, and a stream of air pushed the winning number through a funnel at the top of the machine.

Initially, the April 24, 1980 drawing seemed like any other. The machines were activated, and one after another, a number rose to the top. In this case, the selected numbers were rather auspicious: 6, 6, 6.

The drawing seemed to play out the same way it had hundreds before, but it would later be revealed that Perry had devised a complex scheme to rig the game and win a jackpot for himself.

The big rig

At some point, Perry decided that hosting a lottery drawing wasn't enough; he wanted to win one by knowing ahead of time which numbers would be selected.

He first discussed the idea with brothers Jack and Pete Maragos, his partners in a vending machine business. They agreed to serve as the middlemen who would buy tickets with the winning numbers.

Next, he had to figure out how to ensure that the machines would select his numbers. He approached WTAE art director Joseph Bock for help. Bock figured out that injecting small amounts of white latex paint into the balls would prevent them from rising to the top of the machines.

Bock created a fake set of lottery balls identical to the official ones by using regular ping-pong balls and gluing address-number decals he purchased from a local hardware store onto them. He injected paint into the entire set except for the four and six balls.

Jon Schmitz, a reporter with the Pittsburgh Press, said that the idea was clever because no one watching at home could tell there was anything wrong with the balls. Schmitz said:

When you watched the drawing in full speed motion, and without knowledge of what was going on, it really didn't look obvious to the eye that there was something wrong with the ping pong balls.

Next, Perry had to find a way to replace the real balls with his doctored set. The station's lottery equipment was kept in a locked room at WTAE, which required two keys to enter. Perry had one key, and lottery official Edward Plevel held the other. Perry convinced Plevel to unlock the room and leave long enough for him to replace the official balls with his own.

Finally, to ensure that the balls were switched out after the drawing, Perry brought WTAE stagehand Fred Luman into the scheme. Luman ensured that the real balls were placed back in the locked room and returned the doctored ones to Perry.

The plan worked perfectly, and after the April 24 drawing, Luman got the fake balls back to Perry, who burned them in his office that night.

The big win

At first, the scheme looked like the score of a lifetime. Perry and seven of his co-conspirators collected $1.18 million from the drawing, which would be worth over $4 million today. However, they made one big mistake: They told too many people about the plan.

The April 24 draw had the biggest payout in The Daily Number's history. Winning players collected a total of $3.5 million, which is equivalent to $12.94 million in today's dollars.

Some lottery officials were initially suspicious of the drawing because they saw a large number of tickets purchased featuring different combinations of six and four.

Pennsylvania government officials would claim that they had investigated and found no problem with the game. On April 30, Secretary of Revenue Howard Cohen publicly declared that there was no evidence the game had been rigged.However, there was one group of people that weren't fooled by Perry's plan: the state's organized crime families.

The big boss

Long before the lottery was legalized in Pennsylvania in the 1970s, illegal lotteries known as “numbers games” were extremely popular with state residents. Rather than end their games when the state lottery was formed, the mobsters who ran the games made a small change to ensure their continued success.

They used the numbers from the official lottery as the numbers for their own game so that players would know the drawing was fair. They also increased the size of their payouts to be greater than the state lottery. If you picked the correct numbers, The Daily Number paid out at 500 to 1. The mob games used the same numbers but paid out at 600 to 1 for a winning ticket.

Tony Grosso was one of the state's biggest mobsters in charge of running illegal lotteries. He immediately recognized that the unusual betting patterns meant the fix was in, and someone had rigged the game. He refused to pay any tickets for that drawing, and his suspicions eventually reached state prosecutors, who decided to launch a more intense investigation.

The big bust

The scheme began to unravel when investigators received a tip about the Maragos brothers, who Perry used to purchase large quantities of tickets with different combinations of the numbers four and six.

The two men crisscrossed the state, buying up vast numbers of lottery tickets and spending over one thousand dollars at just one retailer. They also bought illegal tickets from several number runners to expand their winnings.

Investigators learned that on the day of the drawing, the Maragos brothers were seen at a bar in Philadelphia, where they purchased a large quantity of lottery tickets. While at the bar, one of the brothers made a call on a pay phone and, at one point, held up the receiver so the person on the other end could hear the lottery tickets being printed.

The phone call was traced back to the announcer's booth at the WTAE-TV studio. Under questioning, the Maragoes admitted that they had spoken with Perry. After further interrogation, the brothers broke down and admitted their role in the plan. They also implicated Perry and the other people involved.

The Maragoes admitted that they had encouraged their friends and relatives to buy tickets with the four and six-number combinations before the drawing. The massive influx of money on that specific combination of numbers tipped off Tony Grosso and the other number runners that something was wrong with the game.

Eventually, under pressure from prosecutors, the Maragoes brothers agreed to testify against the rest of their co-conspirators, and a grand jury charged seven men for rigging the lottery.

Edward Plevel, the lottery official who helped Perry get access to the lottery balls, went to trial, was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. Bock and Luman both received lighter sentences after agreeing to plead guilty.

Due to their cooperation against Perry, the Maragoe brothers received no jail time. Most of the money they had won had also been recovered.

As the ringleader of the plot, Perry faced the most severe charges. He pleaded not guilty to the case against him, but on May 20, 1981, he was convicted of criminal mischief, criminal conspiracy, theft by deception, perjury, and rigging a publicly exhibited contest.

The judge sentenced him to seven years in prison, but he served only two years and spent another year at a halfway house in Pittsburgh. After his release, he attempted to resume his broadcasting career but was unsuccessful. He held various jobs until he passed away on April 22, 2003, in Attleboro, Massachusetts. Even at the end of his life, he never admitted to rigging the lottery.

In 2000, the movie Lucky Numbers was released. It was loosely based on the Triple Six Fix as the case had come to be known. John Travolta starred as a local weatherman attempting to rig the lottery, and Lisa Kudrow co-starred as his accomplice.

The big ending

Following the discovery of Perry's scheme, the Pennsylvania State Lottery completely revamped its security protocols and introduced much stricter procedures for handling and storing equipment.

Schmitz observed that Perry and his crew could have avoided being caught if they had just kept their mouths shut. He said:

These guys might have gotten away with it, but they let a lot of people in on the fix beforehand. Any good conspiracy is limited to the smallest circle possible, and these guys failed to observe that.

Comments