News writer

Every year, it seems the lottery entices more players, more ticket sales, more jackpots. However, it also brings more debates about whether or not it's a harmless diversion or, for many, a regressive tax by another name.

The latest data from a Lending Tree-Census Bureau analysis shows that in 2023, average per-capita lottery spending in the United States reached about $320. This is a 3.6 - 4.0% increase from the previous year.

If you look at the bigger picture and dig a little deeper, things become more uneven and even troubling.

Suppose you look at states like Massachusetts, where the residents spend about $915 every year on lottery tickets. This is over $300 more than the next-closest state. You have to ask: who is really cashing in?

Some states also have as little as 20% of ticket sales being returned in winnings. Because of this, is it still fair to call it a gamble that people can “play for fun?” We will be looking into those extremes, asking what it says about state policy and incentives, and making a case for why many Americans should reconsider the real cost of hope.

An increase in lottery spending

The average lottery spending was $320 per person in 2023, which may not raise many eyebrows. However, looking at every adult in the states that operate lotteries, the numbers are a lot bigger.

In 2023, there was $108.99 billion in lottery spending, according to LendingTree. This is up from about $103.3 billion in spending in 2022.

Most lotteries are sold through agencies or systems run by the state. These state agencies are benefiting from the “house edge,” or vendor commissions and administrative costs. Whatever happens to be left is used to fund state budgets or designated programs, like education or infrastructure.

This also implies one of two things (or both): more people are playing the lottery, or each player is spending more money on the lottery, or both. Based on the data from LendingTree, the latter seems to be true. Spending per capita is going up, even where populations have remained steady or have declined.

This raises some questions. If the revenue is rising faster than the population, that means the average person is putting more of their discretionary income into lottery tickets. So we ask, is that a rational trade, or is it a danger that people take on without knowing it?

The extremes: biggest and smallest spenders

What makes Massachusetts so strange

Massachusetts is in a world of its own. The average Bay State resident is spending $915 a year on lottery tickets. Not only is it the highest in the country, but it is also over $320 more than the second-highest spender, which is Rhode Island at $573.

What is leading this charge? It could be some aggressive lottery marketing, cultural factors, or even state policies that make access to lottery tickets easier. This type of spending is definitely sending up red flags.

If you think about it, $915 a year works out to be about $76 a month. If you are a household on a tight budget, that $76 could help out with groceries or any emergencies that may pop up. At what point in the process does optimism of winning the lottery turn into reckless spending?

Keep in mind, the Massachusetts Lottery doesn't even have the highest payout ratio for its players. At the same time, it returns about 69.4% of ticket sales in winnings. That still means nearly 30% of what residents spend stays in the different government agencies or commissions before any prizes can be awarded.

Low spenders: North Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma

On the opposite side of things, some states barely register on the data. Which state had the lowest per-capita spending in 2023? That would be North Dakota, which was at $50.16. The bottom tier also included Wyoming ($74.69), Montana ($76.04), New Mexico ($83.79), and Oklahoma ($92.35).

While they had the lowest per-capita spending, some of the states saw the biggest year-over-year percentage increases in lottery spending. We had Wyoming at a 60.6% increase and North Dakota at a 32.8% increase.

Possible factors for the low numbers:

- Income levels and disposable income: In general, states with lower average incomes might find lottery spending less affordable.

- Access and lottery structure: Some states may not have as many stores or do as much advertising.

- Cultural attitudes: A state's demographic, political, or cultural orientation may affect how widely lottery participation is normalized.

- Skepticism or awareness: In some states, people may be more aware of the odds or less enticed by big jackpots.

Whatever the mix, the gulf between top and bottom is remarkable. The top-spending states are pulling in many times the per-person dollars than the lowest states, even though the odds, payouts, and game designs are broadly similar.

Payouts: The uneven returns

A critical piece of the puzzle is not just what people spend, but what they get back. In many areas, the “return on ticket spend” is disheartening.

For the Virginia Lottery, 73.5% of spending was returned to players in the form of winnings. Maine (71.0%) and Missouri (70.4%) also broke the 70% threshold.

Massachusetts, despite its outsized spending, pays out approximately 69.4 % in winnings. That's not terrible compared to many peers, but the subtle issue is scale. A 30% “loss rate” on nearly $900 per person can be far more painful than on smaller spenders.

On the flip side, some states return far less:

- Oregon and South Dakota pay out less than 20% of lottery spending as prizes.

- West Virginia returns ~21.1 %.

- Rhode Island returns ~31.7 %.

That raises a tough question: in states where 80% or more of what you spend vanishes before you even hit a jackpot, is the lottery still a “game of chance” or more like a stealth consumer tax?

For someone spending $300 a year and getting only $60 in winnings (20%), it's hard to rationalize continuing unless the entertainment value is extremely high or their exposure is minimal. But for someone spending nearly $1,000, those losses compound, and the odds of net gain remain overwhelmingly remote.

Is it worth it?

The short answer: for most people, no. Or at least, not in the way we like to frame it.

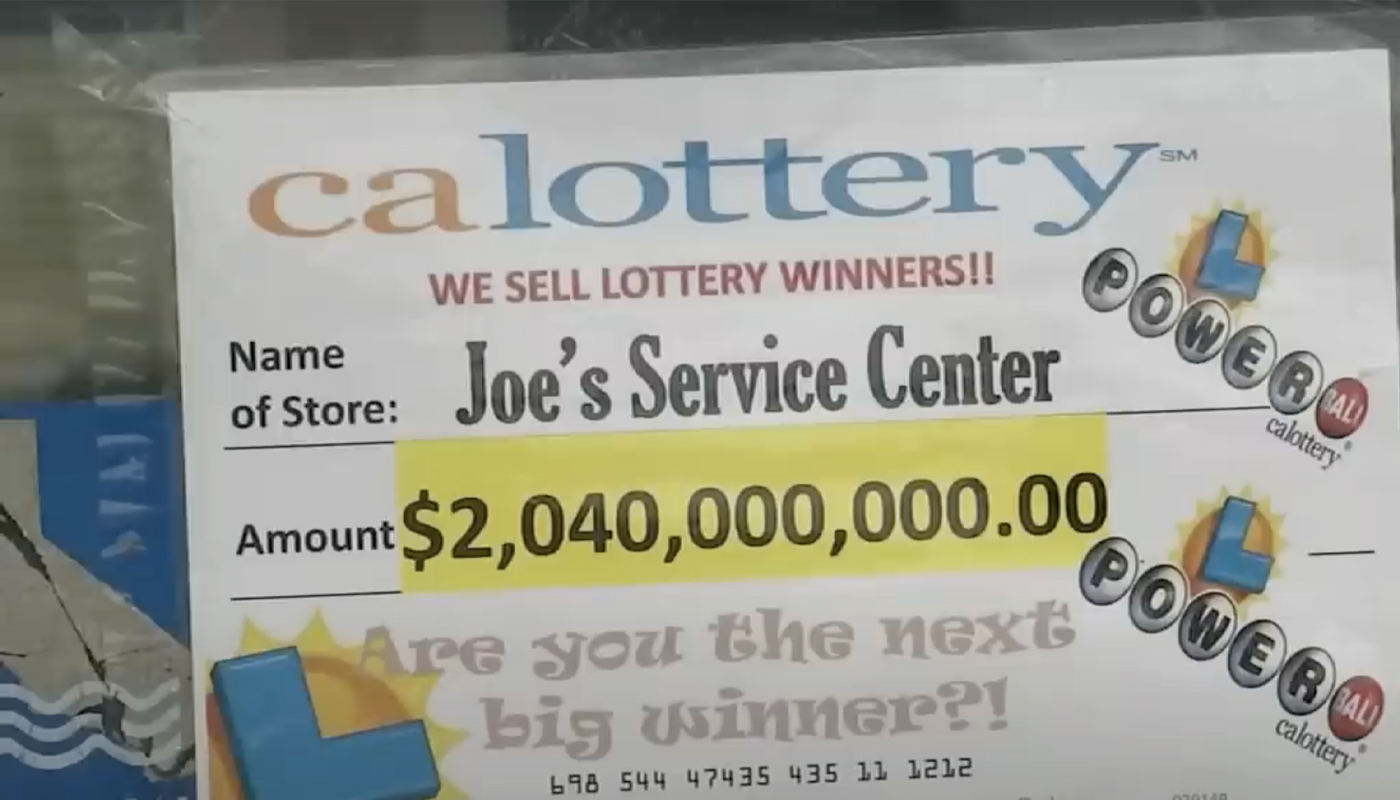

From a behavioral lens, lotteries exploit a combination of hope, optimism bias, and perhaps even gullibility. The chance—even if infinitesimal—of riches holds powerful emotional sway. The messaging is often aspirational: “you could be next,” “dream big,” “this ticket changes lives.” But over time, the expected value for most players is negative after accounting for administrative costs, commissions, and the house “take.”

More rigorously:

- For many players, opportunity cost looms large: money spent on tickets could instead go toward savings, debt reduction, or investments with positive expected returns.

- For lower-income households, lottery spending is regressive: it takes a higher proportion of income from those least likely to absorb the losses.

- For states, the lottery may seem to produce “free money” to fund programs, but in doing so, they implicitly endorse - or even subsidize - an activity with negative expected returns for participants.

Of course, not all lottery spending is blind or reckless. Some individuals treat it solely as entertainment: akin to paying $5 to go see a movie, even though they know they won't see any returns. In moderation, that's arguably defensible. But as spending escalates, and state-sponsored lotteries push more tickets, promos, and fast-play games, the line between casual play and addiction blurs.

In states where payout percentages are extremely low, the rationale weakens further. If only one in five dollars is returned, what social purpose justifies encouraging that behavior? And for those states depending more heavily on lottery revenue — Rhode Island, South Dakota, West Virginia — there is a clear danger of structural dependency: relying on consumer losses to fund basic services.

Policy implications and what can change

If you conclude lottery spending poses real risks to consumers, especially vulnerable ones, what then?

1. Increase transparency and public education

States should always require lotteries to clearly disclose payout percentages, odds, and the “house take” in easy-to-read formats on tickets, websites, and advertisements. Many people play on autopilot; seeing that 80% of a ticket's price doesn't go to prizes might reduce purchases.

Public campaigns, similar to anti-smoking or credit-awareness campaigns, could help shift perceptions. Let citizens see the lottery for what it is, not what they hope it to be.

2. Cap promotional incentives or “loss leaders”

Lottery systems could limit how aggressively they market or discount tickets, especially fast-play games with low odds and low return rates. Reducing the push toward impulse buys might cut excessive spending.

3. Progressive “play limits” or budget safeguards

States might allow or require self-imposed limits (weekly, monthly) or alerts when a person's cumulative spend exceeds a threshold. Similar to gambling responsible-play tools, this would help consumers avoid runaway losses.

4. Adjust payout structures to be fairer

If a state raised average payout percentages (lowering administrative fees or commissions), that would shift more of the burden back to the lottery system and less to consumers. That might reduce the “profit margin” for states but increase fairness.

5. Re-examine reliance on lottery revenue for core services

States whose budgets depend heavily on lottery funds may need to reconsider that reliance. If a significant share of lottery revenue comes from households that can ill afford it, is it sustainable or ethical to lean so heavily on it? States might look to diversify or find more equitable revenue sources.

What readers should take away?

- The average American is spending more on lottery tickets each year, and even modest increases in per-capita spending add up to billions in aggregate.

- The extremes are stark: Massachusetts residents spend nearly $1,000 apiece, vastly more than residents of states like North Dakota or Wyoming.

- Payout percentages vary widely, and in some places, as little as one in five dollars spent becomes prizes.

- For most players, the expected value is negative, and the opportunity cost is real.

- Responsible reform — greater transparency, limits, and structural rethinking — could mitigate harm while preserving the choice to play.

If you're someone who buys a ticket occasionally for fun, treat it as entertainment, keep it small, and don't let dreams outweigh your financial reality. But if you're feeling the pull to chase losses or spending regularly beyond your means, it may be time to reconsider where that hope is getting you.

The lottery sells possibility. But the data suggest most players pay dearly for that possibility, and few ever see fair returns. Big dreams, bigger bills. It's time we saw through the haze.

Enjoy playing the lottery, and please remember to play responsibly.

Comments